My Week in the Yucatán Terrestrial Site - Hormiguero🐜

The journey started at Glasgow Airport, with a 9:35 AM flight to Cancún. Since I live in Lochmaben, this meant a brutal 3:00 AM start but I was packed and excited.

We landed in Cancún around 1:00 PM local time, and Operation Wallacea had arranged a coach to take us to Hotel Adhara, our first overnight stop. The drive gave me my first chance to observe the contrast between infrastructure in Mexico and the UK. Despite less development, people seemed more present, welcoming, and connected to each other in a way that we often miss in digitally-saturated environments.

At the hotel, we cooled off in the in-pool bar a blessing in the 39°C heat and shared laughs about staying put for two weeks. I’m glad we didn’t.

Southbound to the Jungle

Day One - Monday 5:30 AM

The next day began early with a coach journey south—about 8 hours—to the core zone of Calakmul. As we moved further from urban areas, I saw a different Mexico: hand-built stalls on the roadside, tiny homes made of breeze blocks, and power lines like spaghetti. Yet, you’d often see brand-new trucks parked outside, showing how necessity and practicality shape life here.

We finally arrived in Hormiguero, where we met Veria and Emily from Operation Wallacea. My travel buddy, Andrew Walker, had only learned one Spanish phrase before the trip: “¿Dónde está la biblioteca?”—and when we arrived, we actually found the village library. His face was priceless.

From there, we hopped into the back of a black Ford Ranger—scorching hot, naturally—and bumped our way through the forest to our jungle base camp.

First Steps into the Mayan Jungle

The jungle welcomed us with a thunderstorm and a lightning strike so loud and close it made even the staff jump. Just like that, we were in the heart of the jungle ( Note rain Forest (Explain the difference) .

After health and safety briefings (our medic, Alex, delivered the very comforting “If X, Y or Z happens… FIND THE MEDIC”), we were shown to our tents. Andrew and I shared a two-man expedition tent, which quickly turned into a test of patience, friendship, and tolerance for one person's gear explosion.

Dinner that night was traditional Mayan food—rice, beans, spiced vegetables—which hit the spot after a long day of travel and rain.

Camp Life: Wildlife, Mud, and Mosquitos

There’s no twilight in the jungle. One minute it’s light, the next it’s pitch black. With head torches on, we made our way back to our tent, careful not to slip on the muddy limestone paths.

Being from Scotland, I’ve learned that bug nets stay closed and you don’t use lights in your tent, or midges will find you. In Mexico, it’s mosquitos—and giant mutant moths the size of small birds.

Fieldwork: Herpetology and Aguadas

That first night, we had a choice: go on a bat survey or a herpetology transect. I chose herpetology.

Led by Aaron, our expert herpetologist, we hiked around an aguada (a seasonal or semi-permanent natural waterhole that holds water in the dry season and provides critical habitat for animals). These aguadas are lifelines in the jungle.

During the transect, we saw:

Terpin frogs

Cane toads

Various lizards

Possibly even a boa constrictor track

It was humid, buggy, and dark—but absolutely thrilling.

Jungle Nights: The Loudest Silence

Trying to sleep in the jungle is a challenge. The aguada beside our camp came alive at night. Dozens of frogs calling, insects buzzing, and the constant rustle of the canopy above created a wall of sound that felt alive.

The Peeing Story (Unavoidable Jungle Moment)

Middle of the night. I wake up needing to pee. Simple?

No.

It’s pitch black. My headtorch is buried. There’s something the size of a stealth drone moth flapping near the tent entrance. I try to slip out without letting in a thousand bugs. I step into the mud, half-slip, and make the most rushed jungle toilet dash of my life.

I survived. Barely.

Final Reflections

Although I was only in the jungle for one week, the experience was intense, raw, and unforgettable. I learned about:

The importance of aguadas for biodiversity

How climate change is affecting seasonal water patterns

The value of conservation research in remote areas

And, most of all, what it’s like to live and work in extreme, disconnected environments

This week helped me appreciate the resilience of ecosystems, the value of hands-on research, and how stepping far out of your comfort zone can be one of the most rewarding things you ever do.

Day Two – Tuesday | 5:30 AM

If you've ever slept in a tent, you know how "easy" it is to get up in the morning… right? Because you're basically on the floor. It hurts—but in that weird, "this is good for your back" way TikTok influencers rave about.

Bollocks.

Still, I dragged myself out, sore and sweaty, and shuffled over to this makeshift veranda overlooking the aguada. Coffee in hand (yes, they had coffee—it's the little victories), I sat quietly, watching a social flycatcher doing its morning routine. Nest mending, bouncing from branch to branch like it had a full to-do list. A perfect wildlife photographer moment.

Where was my camera?

In the tent.

I told myself I’d enjoy the moment. But as the bird stayed put, almost modeling for me, I cracked. I sprinted back for my camera, powered it on—and… it was gone. Just gone. That bird never returned to that branch the entire week.

But that’s the jungle for you. Sometimes you take a photo. Sometimes the photo takes you.

Morning: Habitat Surveys

We were meant to hike 2 km to a remote transect, but thanks to dodgy radio signals and jungle logistics, Plan B kicked in: Base camp transect.

Now, a transect is basically a defined plot (in our case, 20m x 20m), where we collect detailed data about plant life, tree species, canopy cover, and more. You quarter it, survey each section, and repeat it regularly to detect ecological change over time. Sounds simple—until you’re sweating out half your body weight in the jungle heat while trying to tell one tree from another.

But it was oddly satisfying. It gave context to the jungle around us—turned it from chaos into science.

Lunch? You guessed it: Rice and Beans.

Still delicious.

Afternoon Lecture: What is an Aguada?

We had our first big lecture from Rhiannon, who was heading off to do her master’s in pollination ecology up north in the mezcal-growing region.

She broke down the importance of aguadas—natural or artificial seasonal waterholes formed in low-lying limestone depressions. These were critical to both the ancient Maya and today’s wildlife. Some aguadas are maintained by animals. Others need human intervention to remove debris and keep water levels up during drought seasons. Without them, the forest suffers.

As I sat sweating in the humidity, I realized how vital these muddy ponds really are. Lifelines, not just puddles.

Camera Traps: Citizen Science in Action

Next, we rotated into wildlife camera trap surveys. These motion-triggered devices photograph whatever crosses their paths—ocelots, armadillos, coatis, even the occasional jaguar (if you’re lucky). Our job was to collect SD cards, review footage, and help catalogue what species were where.

It’s research like this that proves to governments and NGOs why these habitats matter. It’s science meets activism—with SD cards instead of protest signs.

Dinner: Rice, Beans… and Tortillas. Spice it up!

Night Transect: Bats!

As we ate dinner, Dave and Itza, our bat experts, were off prepping mist nets along a transect 1 km from camp.

Here’s the thing with bats: there are two main types.

Microchiroptera – the echolocators (think: insect-eaters).

Megachiroptera – fruit bats, who actually see the nets and avoid them.

So catching any at all is a win—and we got 8 species out of 60 known in the region. Incredible.

Of course, we got a little lost on the way, walked double the distance in pitch black, and someone forgot their headtorch (cough Andrew). But we made it and it was worth it. Watching these tiny mammals be gently untangled, measured, documented, then released into the dark was magic.

Highlight? Sleepy Andrew fell asleep mid-bat session, sitting upright, mouth open, while holding a data sheet. Classic.

Day Three – Wednesday | 6:00 AM

Herpetology—the survey closest to my heart.

We headed out on Transect 2, a 2 km jungle trail winding past an ancient Milpa—a traditional Maya agricultural method where they clear and burn a small plot of forest, grow vegetables the first year, then fruit trees in the second. After that? They leave it, allowing the jungle to reclaim it. It’s sustainable, regenerative, and still practiced today.

Even more surreal—we were literally walking over unexcavated Mayan ruins. Mounds of overgrown limestone just waiting to reveal secrets. Between filling out data sheets and flipping over logs, I was full-on living my Indiana Jones meets David Attenborough fantasy.

We saw:

Frogs

Lizards

And one massive millipede the length of a pencil

Lunch: Yep, Rice and Beans (still not sick of it).

Lecture: Maya People & Farming Conflicts

This one hit different. It explored the balance between indigenous agricultural rights and conservation efforts. Turns out preserving a forest isn’t as simple as saying “leave it alone”—not when people have lived with, and from, it for generations.

Afternoon Habitat Transect (I skipped – rest is sacred).

Dinner: Rice, Beans… AND Chicken!

A feast. Spirits were high.

Night Transect: Herps Again – Red-Eyed Tree Frog Time

This was special. Our local Maya guide, Izicel, joined us. With just his ears, he honed in on the distinctive chirp of the Yucatán red-eyed tree frog—and boom, there it was.

Also with us? Suzi, a young aspiring herpetologist from down south. Earlier that day, I’d shown her how to shoot on manual mode with her camera. And as she crouched in the mud, photographing this frog like her life depended on it, she was shaking with excitement.

We both were.

I got the shot. So did she. One for the books.

That night, I went to bed buzzing. Jungle nights are loud—buzzes, croaks, distant howls. But I’d never felt so quiet inside. Fulfilled. In awe.

And this was only day three.

Day Four – Thursday: The Calakmul Ruins

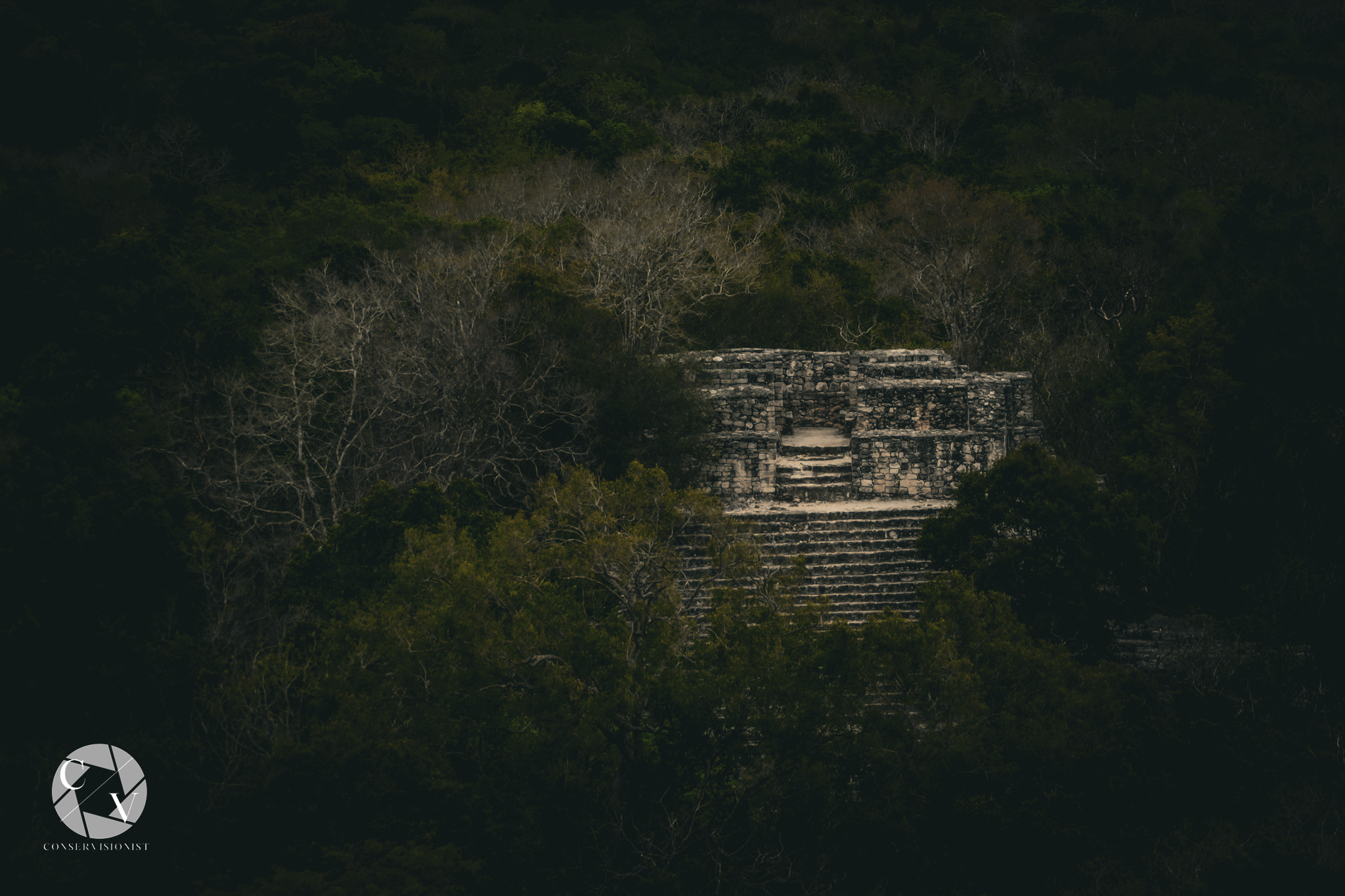

On the fourth day, we had the amazing opportunity to travel to the Zona Arqueológica de Calakmul. These Mayan ruins were excavated in the 1980s but were first rediscovered in 1931 by Cyrus L. Lundell, who was conducting aerial surveys in the Yucatán.

On the way there, we passed over the Tren Maya (Mayan Train). It’s a 900-mile-long monstrosity that crosses southern Mexico, allegedly to boost tourism. But all we saw were freight trains. I can't even begin to explain how much jungle was cleared to make room for this track. We’d seen it back on Day One during our 8-hour journey in — and now again. It cuts straight into the core of the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve.

But I digress.

After a long two-hour bus journey — with air-con — I realized I’d acclimatized somewhat because I was freezing. And I’m Scottish! That says a lot.

We passed KM20, another of Operation Wallacea’s campsites, and arrived at the ruins. There was a small museum attached, with replicas and artifacts from the temples. And… it had Wi-Fi. Honestly, the moment “Wi-Fi” was mentioned, every Millennial and Gen Z’er flocked to the signal point faster than mosquitoes go for ankles. But even a short moment of contact with home was welcome — if only to let my partner Ruaridh know I was alive and would eventually come back.

The site has three main temples. It was explained that this place was the last known stronghold of the ancient Maya. The structures made up a marketplace, a palace, and a burial temple. Unlike historical sites in the UK or elsewhere, here you’re allowed to climb them — respectfully, using designated paths to reduce erosion.

At first, there’s a moment of hesitation — it feels like you’re doing something you shouldn’t. But I truly believe that being able to physically climb these ancient monuments creates a stronger understanding and connection. It reminded me of the Scandinavian approach to history — hands-on and alive. And one thing you quickly notice as you climb? The Maya had small feet. The steps were short and incredibly steep.

It was awe-inspiring. We climbed three temples, each offering more spectacular views. From one, you could see a distant ruin across the canopy — a tiny speck. That was Guatemala. Mind-blowing.

I felt privileged not only to witness this site but to feel it — to become a small part of its ancient presence, if only for a few hours.

The bus ride back? Cold. The air-con had gone from friend to foe.

Dinner was late, but the kitchen team had stayed behind to feed us — rice and beans, warm and appreciated.

That night we rested. It was a physically demanding day, but absolutely unforgettable.

Day Five – Friday: Wet, Wet, Wet (The Day I Missed Home)

This was the day I really missed home. Maybe it was the quick Wi-Fi check-in with Ruaridh, or maybe just the relentless rain — but I was feeling it.

I missed cuddling my dogs. I missed being able to flick a kettle on without waiting 10 minutes for boiling water. And putting boots on in that clay-like mud had gone from novelty to mental challenge.

We didn’t do much. Spirits were low. It rained all day.

However!

In a rare 5-minute break from the downpour, Suzi and I got to talking. We were sharing herpetology dreams — what we most wanted to see next. We both agreed: the Mexican burrowing toad.

These strange, moisture-dependent amphibians spend most of their lives underground. You hardly ever see them. We could only hope.

But then... it had been raining for about 15 hours straight. As darkness fell and the rain paused again, we heard something that stopped us in our tracks.

A sound — loud, pulsing, surreal. The only way to describe it is like standing on the racetrack during the MotoGP. This wall of sound: kneewm-kneewm-kneewm — everywhere.

At first, I wasn’t sure. But then we looked down and there they were — the Mexican burrowing toads. Hundreds of them.

What are the bloody odds?

The rain, the season — it had all aligned. They had emerged to breed. It was a spectacle I’ll never forget. Mostly because, for once, none of us could hear anything over the noise. Nature was roaring.

Day Six – Saturday: Snakes & Serendipity

The magic of the previous night lingered. I no longer minded the rain — it clearly brought out wonders.

After breakfast and a few lectures, we had time to sort camp — mostly digging trenches to stop our gear (and us!) from floating into the aguada. The Opwall staff were amazing, doing everything they could to keep things functioning. We all pitched in.

Later, Suzi and I reflected on the previous night and dreamed up our next wish: snakes.

The Yucatán is full of them — arboreal, terrestrial, venomous, non-venomous. The coral snake, the speckled racer, and the Mexican cat-eyed snake, to name a few. We hoped aloud that Aaron, our herpetology lead, might help us spot one.

And — as if the jungle was listening — we got lucky. Again.

That night’s transect had us reopening an old, overgrown route. Lexi, the camp medic, led the charge with a machete, looking like something straight out of an action film. I was giddy — cutting through untouched jungle, the sense of adventure was real.

Then Aaron stopped the group.

Urgently asked for the ID book. The research assistant seemed so surprised he forgot he had it on him. Finally, they flipped to the page: a snake.

It could be one of the most dangerous in the area — or its harmless mimic.

The professionals stepped in, assessed the pattern. Our hearts were racing.

It was the milk snake — the mimic. It had evolved to resemble the venomous coral snake almost perfectly. A marvel of biology and evolutionary pressure.

And we got to see it. Up close. Vibrant, bold, beautiful. Anything but "simple."

But that wasn’t all.

Further along the transect, we found a Mexican cat-eyed snake — long, slender, hunting in the vines. James, one of our professors, was ecstatic. He’d been searching for arboreal life all night, and here it was.

Watching him, I had this sudden realization: for all his vast experiences — and there have been many — these moments still moved him. That’s what conservation is about. Not just seeing wildlife, but understanding it. Feeling it. Connecting to it.

I went to bed glowing. Full of wonder. Full of gratitude.

Day Seven – Sunday: The Last Day

This was hard.

In just one week, we’d become a jungle family. No signal. No distractions. Just nature, science, and each other.

We’d walked, learned, sweated, laughed, and struggled together. And now it was ending.

There was a final social gathering that night, but unfortunately, my body had other plans. I got ill. Cramps, exhaustion — I had to lie down in my tent, feeling sorry for myself.

But — before that happened — I had built the fire. That same fire everyone gathered around. And even though I wasn’t there, I felt like I had contributed to that final moment.

Day Eight – Monday: The Bus to Akumal

And just like that, it ended the same way it began: in the back of a pickup truck.

At 5 AM, we rolled off toward the village, waving goodbye to camp.

It felt surreal. Gutting.

The staff still had eight more weeks in the jungle. I wanted to stay. I really did.

But our next stop was Akumal — and the story was far from over.